This post is the first half of a broader discussion on classical reception in Dragon Age.

The Chantry teaches us that it is the hubris of men which brought the darkspawn into our world. The mages had sought to usurp Heaven. But instead, they destroyed it.

(BioWare, 2009)

These, the opening words of the first game in the Dragon Age series introduce the central conflict of the game: the invasion of fantasy monsters (Darkspawn) in a regularly-occurring “Blight” that was brought on by “the hubris of men”. Soon enough, however, fans of the series find that it is not the hubris of all humans which was the issue, but instead the hubris of the citizens of the Roman-coded Tevinter Imperium. A series (so far) of three games that began with Dragon Age: Origins (hereafter Origins) in 2009, followed by Dragon Age 2 in 2011, and Dragon Age: Inquisition (hereafter Inquisition) in 2014, the franchise is known for strong characters, player choice, and a morally-grey storyworld. Yet the Tevinter Imperium is frequently discussed within the series in terms of good and evil, as a once-powerful empire that conquered most of the gameworld and continues to practice slavery and human-sacrificing blood magic which are seen as unequivocally evil to many outside the Imperium. In quest design, too, Tevinter and its citizens are frequently antagonists, whether as a group of slave traders tricking an entire community of impoverished elves into enslavement in Origins, or as the antagonist of Inquisition who seeks to restore Tevinter to its age of glory (and destroy the world while doing so). The Tevinter Imperium, a once-powerful empire that is now in decline, is reinforced to the player as a site of danger, a place consumed by its former greatness even as those within the Imperium scheme and undercut the nation itself.

This, the first of two blog entries that address the coding of the Tevinter Imperium as Roman, will focus on establishing this correlation before turning to the franchise’s use of the traditional “decline through decadence” narrative that so often pervades discussions of the Roman Empire in popular culture. In the second entry, I will turn my attention to the characters of Dorian Pavus and Cremisius Aclassi, two queer characters from Tevinter who directly counter connections of Rome’s “decline” with the moral decline often touted in popular discourse in order to support contemporary homo- and transphobic ideas. Thus I will demonstrate the way Dragon Age‘s sophisticated reception of Rome both works with popular ideas of Rome’s decline and works to challenge those very ideas.

Indeed, by coding Tevinter through language, cultural structure, and narratives of “decline through decadence” as Roman, the Dragon Age franchise uses Tevinter to counter common appearances of Rome in video games, both representations of Rome itself and through its coding in the fantasy genre, that often include narratives of imperial greatness. As Lowe writes on Rome in video games: “[it] is often seen as having grown almost unstoppably from a single settlement into the largest empire in the known world: history’s most obvious ‘win’” (2009, 78). Indeed, in the medium of video games, Rome has now become ubiquitous with strategy games, including Rome: Total War (2004), Imperator: Rome (2019), and Centurion: Defender of Rome (1990) among many others. As games which often manifest as colonial power-fantasies, these strategy games put players in charge of a Rome as it seeks to expand, and reward the player for conquest and colonization. (For more on replications of European imperialism in video games, specifically in strategy games, see Mukherjee, 2017).

Even when Rome is used as it is in Dragon Age, with cultural elements transplanted to semiotically reflect fictional empires, it is largely structured as a force for good. In a video game outside the franchise, Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (hereafter Skyrim), for example, the Roman-coded Cyrodiil Empire is set as a multicultural force for peace fighting against the overtly-racist Stormcloak rebels. Indeed, the Stormcloaks have been adopted by White Nationalist organisations, such as Stormfront, as an avatar of their cause (see Bjørkelo, 2020). By contrast, the Roman-coded Cyrodiil Empire is overtly multicultural and inclusive, whose religious intolerance may seem a small price to pay for “stability” and “security”. Indeed, Imperial control in Skyrim reflects a more pro-Imperial approach similar to those expressed by scholars like Howe:

At least some of the great modern empires … have virtues that have been too readily forgotten. They provided stability, security, and legal order for their subjects. They constrained, and at their best, tried to transcend, the potentially savage ethnic or religious antagonisms among the peoples. And the aristocracies which ruled most of them were often far more liberal, humane, and cosmopolitan than their supposedly ever more democratic successors. (2002, 164).

Thus the coding of the Cyrodiil Empire as an imperial force for good alongside the trappings of Rome reflects a more common pattern in video games in which Roman imperialism is idealised.

While this is certainly the tendency in video games, the idealization of Roman imperialism is not universal. In Fallout: New Vegas (2010), for example, a post-apocalyptic gang of thugs calling themselves “Caesar’s Legion” and modelling themselves after their idea of Rome are widely feared for their conquest, crucifixion, and enslavement of others. Assassin’s Creed: Origins (2017), meanwhile, represents the Roman presence in late-Hellenistic Egypt as being deeply corrupt (Cameron 2020). In The Forgotten City (2021) meanwhile, the player can challenge a Roman magistrate about various customs, including slavery and gender inequality. Yet these are exceptions rather than the rule.

Although Fuchs et al. (2018) have argued that Dragon Age represents an imperialist narrative by embracing a model of game-design predicated on imperialist ideas of exploration and discovery, through the franchise’s representation of Roman/Tevinter imperialism, I argue that Dragon Age too is one of these exceptions. By seeding both the institution of slavery and the history of imperialism in the Roman-coded Tevinter Imperium, the franchise reminds players that the “obvious ‘win’” of ancient Rome is indeed a win only for some, and an experience that leads to centuries of cultural and personal trauma. In the series’ fictional setting of Thedas, various nations stand as clear analogues for real-world medieval European cultures. Ferelden – the setting of Origins – is clearly England, from the broad accents to the elite social structures; Orlais – one of several settings in Inquisition – is notably France; while the Free Marches – the setting of Dragon Age 2 – aligns nicely with the Italian Free states. Often referred to casually as “the Imperium”, Tevinter is thus a clear analogue for Rome.

This is flagged at least initially through linguistics, as many of the nation’s institutions and individuals are given Latin-based names: the Altus (“high” or even “deep-rooted”) are the first mages of Tevinter who now make up the “upper crust of Tevinter nobility” (BioWare 2013, 77); the Magisters (“masters”) who rule Tevinter as part of the Magisterium; the Soporati (“sleepers”), or non-magic-using citizens are just a few examples. The position of quastor in Tevinter is indeed similar to that of quaestor in the Roman Empire, described as “[c]ounting numbers and shuffling papers all day…”. Even the Tevinter companion, Dorian Pavus, takes his name “Pavus” from the Latin for “peacock”, while the MacGuffin of the Netflix show, Dragon Age: Absolution (2022) is the circulum infinitus.

Beyond naming conventions, Tevinter is architecturally coded as Roman too. There is a famous (but now crumbling) Imperial highway that once connected all corners of the empire, and while its architectural style is not Roman or in any way “classical”, the capital city is renowned for its stonework and architecture, while a massive arena sits at that city’s centre, reflecting what Lowe once observed, that: “The Colosseum as shorthand for Rome is most prominent in video games…” (2009, 76-77).

Moreover, the history of Tevinter clearly codes it as a Rome in decline, as much of the territory of Thedas was once ruled over by the Tevinter Imperium in its heyday centuries past. Tevinter ruins are scattered throughout the game for the player to explore, an ever-present reminder of this imperialised past. The first event for all players in Origins, in fact, the disastrous Battle of Ostagar (an event referred to as a common touchstone in every later game), is set in and introduced to the player as a Tevinter ruin. Dragon Age 2, in fact, which is largely set in the independent city, Kirkwall, has notably Tevinter architecture, and the final battle of the game sees the player face off against animated stone statues of people enslaved to Tevinter. Thedas has thus been an historical victim of Tevinter imperialism, just as Europe had been of Rome, and evidence of Tevinter’s dominance remain as a constant reminder of this fact to both the player and residents of Thedas within the game. Indeed, through this ever-present evidence of Tevinter’s past conquest, the history of imperialism is shown to the player to have functioned as “an act of geographical violence through which virtually every space in the world is explored, charted, and finally brought under control” (Said, 1993, 271).

Indeed, Tevinter’s imperialism is directly linked with the regularly-occurring Blight, a near-apocalypse that is resisted by the player in Origins. Only created through the sacrifice of hundreds of enslaved people, the First Blight was caused when:

The Imperium’s power was at its peak … The civil war had ended. The Magisterium was united, its armies scooping up bits of Thedas like candy. …it was a demonstration of how exceptional Tevinter had become.

The First Blight that resulted extended for almost two-hundred years, destroying much of Tevinter and marking the beginning of the end of the Imperium’s dominance. And this near-apocalypse returns regularly, leading to calamitous effects on a global scale. Thus, in Dragon Age, the result of imperial domination is realized literally as a regularly-returning force of monsters who seek to destroy the world.

Tevinter’s slavery, too, is a source of fear and disgust for many, and it is outwardly associated with the Imperium; as the player-character states in Inquisition: “Anyone who talks about the Imperium mentions slavery.” Outlawed throughout much of the rest of Thedas, Tevinter’s slavery is particularly coded as Roman, as well. Certainly, many enslaved people in the Imperium are Elven, thus lending it a racial dimension at times. Yet this is based on historical conquest rather than a racialized institution, as many races are seen enslaved in Tevinter, while Elves similarly hold positions of privilege as mages in the Imperium. Moreover, once an enslaved person has been freed in Tevinter, there is a clear continuing social bond of obligation that exists between a formerly enslaved person and their former owner, resembling the libertus/patronus relationship. Indeed, the formerly-enslaved sister of Fenris, a character companion in Dragon Age 2, clearly still owes service to her former enslaver as his apprentice as she helps track down her brother and attempts to return him to servitude. In Dragon Age: Absolution (2022) meanwhile, the protagonist, who had once been freed by her enslaver, just as her Roman counterparts, can easily be re-enslaved as she had not been freed officially in front of a magistrate, and thus her enslaver can easily retract her freedom.

Finally, Tevinter’s “fall” is linked to theories of Rome’s collapse found in 19th and early 20th century historiography: its decadence. (Of course, the suggestion that Rome “fell” has been rightly challenged by scholars of Late Antiquity beginning with Brown). Perhaps best encapsulated in Couture’s 1847 painting The Romans in their Decadence, many historiographers looked to ancient historians themselves, including Sallust, Livy, and Tacitus, who establish an idealised Rome to set in contrast to their morally “inferior” present. As Sallust explains:

But after the state was corrupted by extravagance and idleness, the republic still managed to endure the vices of its generals and even its magistrates thanks to its vastness, but just as if the force of its ancestors were exhausted, for a long time there was clearly no one at all who was influential at Rome because of his virtue.

Catilinae Coniuratio 53.5

Scholars and writers working into the 20th century thus saw in the decline of Rome a link with its apparent decadence, inspired by these Roman writers, and Gibbon’s suggestion that Rome’s fall was caused by the “opulent nobles of an immense capital, who were never excited by the pursuit of military glory, and seldom engaged in the occupations of civil government” (3:310). Indeed, this opinion, at least in popular culture if not in academia, persisted through the 20th century, with French historian Chaunu once claiming that: La décadence, c’est Rome (“decadence, it is Rome”) (1981, 165), (for readers interested in this myth, Theodore is an excellent study). Films like Scott’s Gladiator (2000), too, buy into this narrative by contrasting the “decadence” of the Emperor Commodus with the protagonist, Maximus, who epitomises Roman virtus as an active general and paterfamilias.

In Dragon Age, Tevinter is painted with a very similar brush. The Tevinter companion, Dorian, frequently comments on this stereotype, often sarcastically: “…filthy, decadent brutes, the lot of them!” and complaining “Nobody’s peeled a grape for me in weeks.” Indeed, in summarizing the relationship between himself and the Orlesian mage, Vivienne, Dorian comments: “I mock Orlesian frippery and nonsense, you mock Tevinter decadence and tyranny.” Thus the apparent decadence of Rome in its supposed fall defines the Tevinter Imperium too, and is one of its central stereotypes.

Clearly, Tevinter is coded as Roman, and many of the elements that code Tevinter as Roman are directly connected to the fear others in Thedas have for the Imperium, who see in its imperial ambitions apocalyptic effects and enslavement. Indeed, the first encounter many players will have with Tevinter in Origins is preventing the enslavement of a community of City Elves living in Ferelden, while the Netflix show, Dragon Age: Absolution provides our first glimpse of Tevinter itself through the eyes of its formerly-enslaved protagonist. Thus not only is Tevinter coded as Roman, but that very coding is central to its villainy.

Yet the player does not merely witness the reactions of others to Tevinter, but as an active agent within the storyworld – one in which player choice is notably a selling point – they must also pass moral judgment as the player-character. Through gameplay, therefore, the player is encouraged to view Tevinter with suspicion. In role-playing games, like Dragon Age, memory has been identified as a key component of narrative immersion for the player (see Whitlock, 2012 & Moran, 2012). This functions not only over a series, where a player of Inquisition who has played Origins will likely remember the Tevinter enslavement questline, but also through the origins of an avatar, which allows the player to “become the character to some extent, losing self in the cloak of the character” (Whitlock, 2012, 150). And Dragon Age titles are particularly interested in this element of character creation. In Origins and Inquisition, player-character origins directly affect the reactions of other characters to the player within the game.

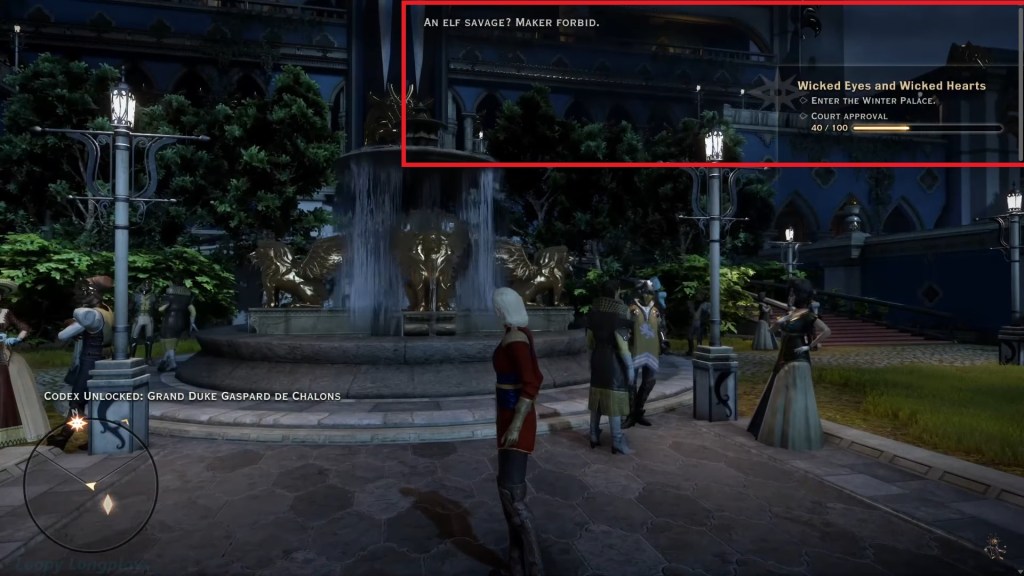

When visiting the Winter Palace in Orlais in Inquisition, for example, the player must gather “court approval” by behaving according to Orlais’ complex cultural norms, but they lose significant influence immediately on arrival if they are anything other than a human noble. An Elven, Dwarven, or Tal-Vashoth, or human mage Inquisitor will not just witness discrimination but will experience it first hand, being forced to work harder to make up for the influence lost because of their very identity. Thus choices in character design are not simply aesthetic, but reflect unique character perspectives grounded in that character’s standpoint.

In Origins we see this directly affecting the player’s reaction to Tevinter particularly through the Roman-coded institution of slavery. Featuring six unique opening sequences (often taking one to two hours to complete), a popular background for players is the “City Elf” origin. In this prologue, the player’s avatar is an Elf and begins their story in the very Elven slum that Tevinters later try to enslave. Thus, when the player returns to this slum after hours of gameplay only to find many familiar characters being enslaved, including the player-character’s own father, the player is given a personal stake in this conflict. Through gameplay that incorporates character identity, the Dragon Age series thus harnesses the importance of memory in player decision-making throughout the game. For the player whose avatar experienced the indignities of life in an Elven slum, including extreme violence and rape, the enslavement of those Elves later by Tevinter will hit hard, causing a more visceral reaction against the Imperial enslavers because they have been allowed a certain perspective within the storyworld.

Moreover, in a franchise notorious for its player choices, it is notable that it is difficult for the player to align themselves ideologically with Tevinter without being punished for it. In the enslavement questline in Origins, for example, if player choose to allow the Elves to be enslaved, you will lose favour with more of your companions (five) than if you help to free the Elves (one, under very specific conditions). In Inquisition, moreover, when speaking with the Tevinter, Dorian, about his culture, his culture is treated as “Other” for the player-character to discover and learn about as the player does. In the Dragon Age franchise, Tevinter’s coding as Roman layered with the player’s experiences with Tevinter that directly reflect this Roman coding, thus establish imperialism as something to be resisted.

Dragon Age therefore offers a sophisticated resistance to imperialism predicated on a player’s understanding of Rome (and thus recognising it in Tevinter) that uses those very Roman structures (slavery and imperial expansion) to undercut the glorification of empire often seen in modern video games. Thus we see throughout the Dragon Age franchise that the memory of empire, both externally as Rome and internally as Tevinter sets the stage for a warning about imperialism and its glorification.

Natalie J. Swain is an assistant professor at Acadia University, Canada. Her research interests include Latin elegy, philology, and narratology, and Classical Reception in modern comics, video games, and narratives of the Polar Regions. Natalie has published and spoken extensively on all of these topics, most recently in Classical Philology and Games and Culture. Natalie is actively involved in the Classical Association of Canada’s Women’s Network, is a founding member of Antiquity in Media Studies, and is actively involved in union-work and fighting for better conditions for contingent faculty, PhD students, and early-career scholars.

BioWare (2013). Dragon Age: The World of Thedas, Vol. 1. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Books.

Bjørkelo, Kristian A. (2020) “’Elves are Jews with Pointy Ears and Gay Magic’: White Nationalist Readings of The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim.” Game Studies 3: Retrieved from https://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/bjorkelo. Accessed on 26 April 2023.

Brown, Peter (1971). The World of Late Antiquity. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Cameron, Hamish (2020). “’Scuttle back to your wine you sacks of uselessness’: The Roman Army in Assassin’s Creed: Origins.” [Paper presentation]. Antiquity in Media Studies, virtual conference. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/UbRPxHuASbI. Accessed on 9 August 2023.

Chaunu, Pierre (1981). Histoire et decadence. Paris: Perrin.

Fuchs, Michael, Vanessa Erat, & Stefan Rabitsh (2018). “Playing Serial Imperialists: The Failed Promises of BioWare’s Video Game Adventures.” The Journal of Popular Culture 51.6: 1476-1499.

Gibbon, Edward (1909-1914). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, (John Bagnell, ed.). London: Methuen.

Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lowe, Dunstan (2009). “Playing with Antiquity: Videogame Receptions of the Classical World.” In Dunstan Lowe & Kim Shahabudin (eds.), Classics for All: Reworking Antiquity in Mass Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 64-90.

Moran, Chuck (2012). “The Generalization of Configurable Being: From RPGs to Facebook.” In Gerald Voorhees, Josh Call, & Katie Whitlock (eds.), The Digital Role-Playing Game. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group: 343-361.

Mukherjee, Souvik (2017). Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing AG.

Said, Edward (1993). Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus.

Theodore, Jonathan (2016). The Modern Cultural Myth of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Whitlock, Katie (2012). “Traumatic Origins: Memory, Crisis, and Identity in Digital RPGs.” In Gerald Voorhees, Josh Call, & Katie Whitlock (eds.), The Digital Role-Playing Game. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group: 135-152.

One thought on “A Warning Against Imperialism #1: The Tevinter Imperium as Rome in Dragon Age. By Natalie J. Swain”