Chants of Sennaar (2023, Rundisc) is a game about learning glyphic languages through puzzles and interactions. That’s about all I can tell you before I get into spoiler territory, so now’s your chance – go play, then come back.

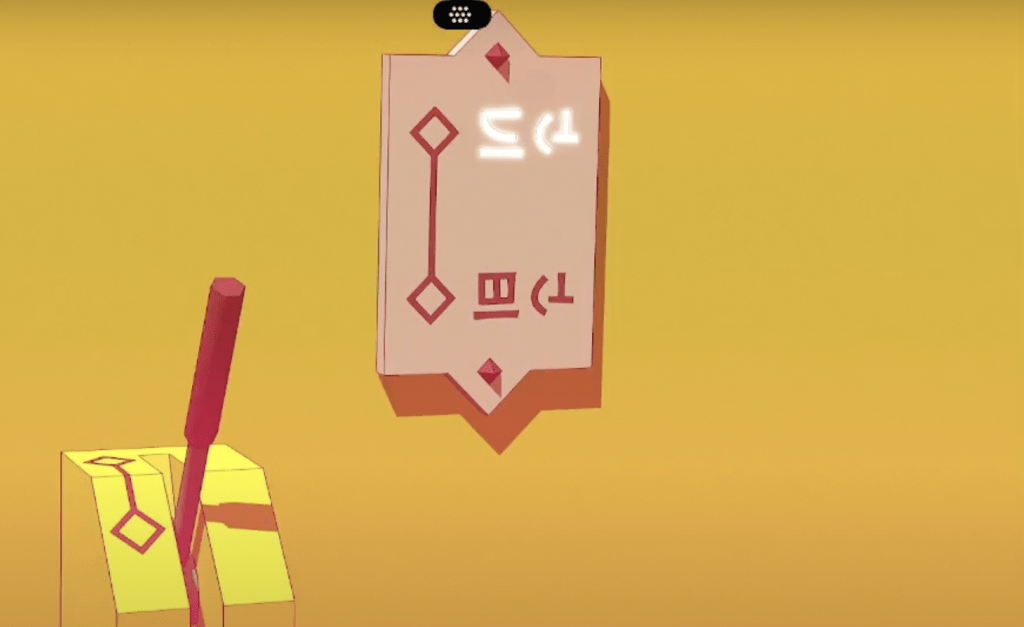

Your first puzzle in Chants of Sennaar teaches you the main mechanic of the game: the glyphs marking a lever next to a door “open” and “closed” which you learn from context. Move the lever to “open”, and, voila, the door opens. Cleverly, the game includes a journal where you can track all your knowledge, and even confirm it with pre-approved translations from the game’s writers.

But Chants is not just a game about the intricacies of a single language. Instead, this nigh literal tower of Babel has five layers of societies, each with their own corresponding glyphs. These glyphs can (and indeed, must) be translated from one set to another in order to complete the game.

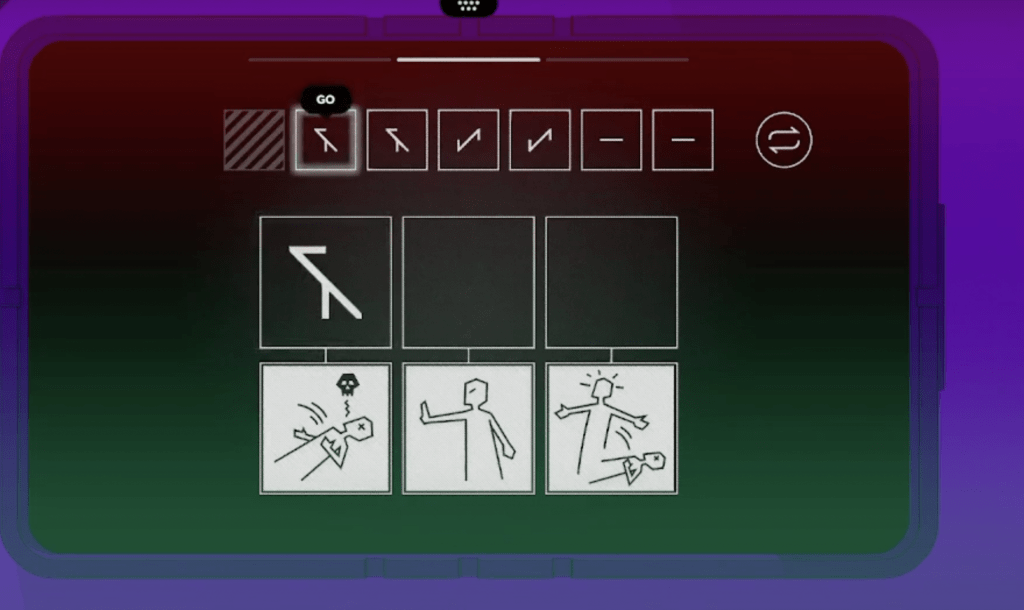

But you don’t have time in a 9–10 hour game to learn five whole languages! Indeed, you won’t have to. The glyph sets for each society are made up of meaning-units only, no sound required. Even when characters in the game speak, you see their words in glyphic speech bubbles you can replay at will. And you will only see about 30 glyphs out of however many might be possible in each.

This is not Heaven’s Vault (2019, Inkle), where the Ancient language has several dozen glyphs that combine in sets to make each meaning, like a long-form version of Chinese hanzi.[1] Chants prefers a simpler structure for a more environmental puzzler of a game. One glyph corresponds roughly to one word, but you have five glyphs to learn for each. More or less.

Given that, the glyphs could have looked like anything at all. They could have been straight pictographs, or random swirls, or colored dots. Instead, the designers chose to make systems of writing that tell you a surprising amount about the culture that created them and the ways in which meanings are connected.

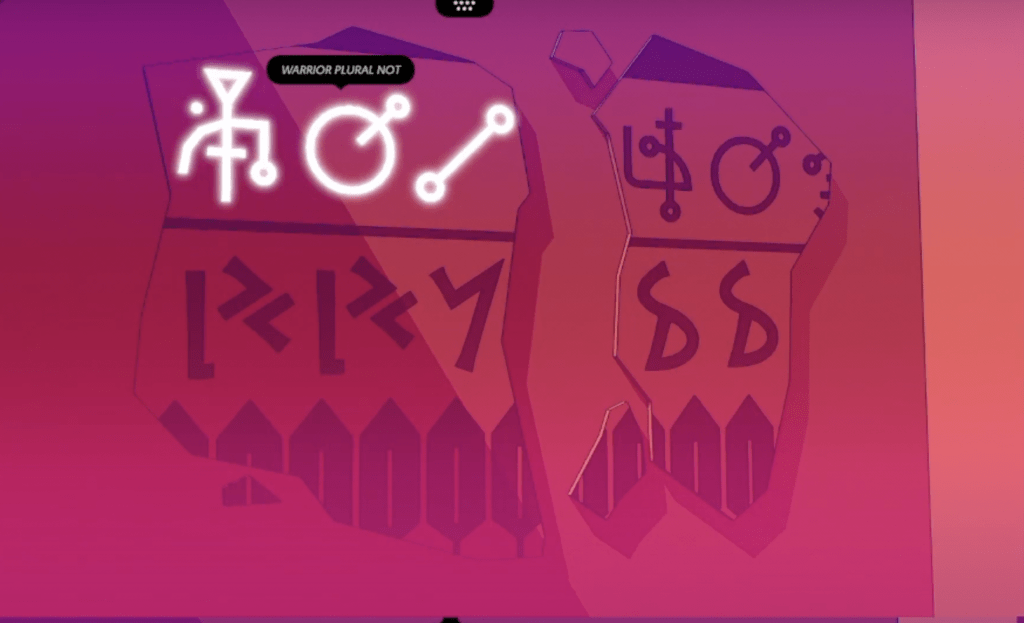

For example, nearly every set of glyphs in this game has a set of identifiable characteristics to tell a noun from a verb. On the first level, the Devotees, a horizontal line at the bottom of a mark indicates a verb, and a curved line to the left indicates a basic noun. But also, a person is indicated by a truncated L shape on the left, and a building or location is indicated by a square around the glyph open to the upper left. When you enter the second level, the Warriors, a verb is indicated by a V shape at the bottom of the sign, and a person by a Y shape in the center, but other nouns don’t necessarily carry such a visual marker. The Bards on the third level indicate place by a dot below the line of the glyph, and make a distinction between a sickle-shaped mark for types of people and a J shaped mark for pronouns. And so on.

The morphology of each can also lend meaning, in a nod to pictographic scripts. The Devotees’ sign for greetings looks like a hand waving, which they also demonstrate a character doing the first time you see it. The upside-down Y shape in the Warriors’ word for Devotees, which your omniscient journal confirms translates to Impure, signifies their disdain. Even the Anchorites’ stylized glyphs hold some amount of this, with signs combining meaning to form more complex ideas, as some of the gameplay in that level asks you to demonstrate; the sign for “me” plus the sign for “plural” makes the sign for “us”.

The form of each writing system is also telling. The Warriors’ jagged lines, refusing any curves at all, mirrors their aesthetic, which favors planes and sharp points, and their culture, with its rigid hierarchy. The flowing style of the Bards’ glyphs hints at their devotion to beauty in all things, but the consistent line beneath hints at the inevitable undercaste who support such a lifestyle. The Alchemists’ writing, the only system with a full set of numbers, balances angles, curves, and circular dots which would be nearly impossible to consistently write by hand, recalling real-world alchemical symbols. And the Anchorites, whose lives revolve around computerization, have a system that works on a set of predetermined linear paths, like an old segmented LED clock display.

Perhaps most importantly for storytelling, each language includes a single glyph that indicates what that society holds most dear, and each one is a variation on the same sign, a flattening of a doubled tetrahedron. For the Devotees, it is their god. For the Warriors, duty; for the Bards, beauty; for the Alchemists, the Key, or Philosopher’s Stone. And for the Anchorites, the symbol is Exile, the demiurgic AI who has fragmented the tower. This is the enemy that you, a created being climbing the tower to its peak, must fight, not with power, but with the ability to communicate and build community.

Well, also with stealth.

Because the way you win is by translating between the different peoples of the tower. The Warriors love music, which is why they worship the Bards. But you can translate for the Devotees below and let them tell the Warriors that they, too, have music, which opens the gates of friendship. The Bards feel alone in the world, cut off from others in isolation. But you can open lines of connection that allow the Alchemists to make a gondola to connect their two levels, rejoining what was broken.

Interestingly, the designers added a fairly realistic twist to the simple one-to-one translation that you must do. Even though many meaning-units are the same from one language to another, the syntax differs.

A good example here is the style of pluralization in the first three languages. In the Devotees’ language, glyphs are reduplicated to show a plural. Instead, the Warriors and the Bards both have a separate symbol to indicate pluralization, but the warriors put the plural marker before the affected noun, and the Bards put it after.

Most of the syntactical changes are of that nature, a pluralization style switch here, a modifier placement there. But the most radical shift in expectation comes from the Bards’ language, which alone of all of them has a totally shifted word order. Instead of the familiar subject, verb, object order, as you’d find in English, the designers chose object, subject, verb order, the rarest type in all world languages. According to a global survey performed in 2016, just 19 languages from a single language family primarily use this syntax.[2]

The developers of Chants of Sennaar have made it clear that they took their influences from all over the world, both ancient and modern languages, art styles, and architecture. In one piece written by co-designer Julien Moya, he indicates a deep awareness of how culture shapes language, saying:

“A language reflects the culture it comes from in many ways. Its graphic aspect reflects its history, the technologies that have shaped it, and the influences that have enriched it. The corpus of words, the vocabulary used, says much about the way its speakers see the world, their values, prejudices and taboos. Finally, the very syntactic structure of a language can serve to express its more or less primitive character or, on the contrary, its subtle or poetic nature.”[3]

He also acknowledges that he and his co-designer, Thomas Panuel, are not linguists. They are game designers. Like Jon Ingold, the creator of Heaven’s Vault, Moya and Panuel wanted to create something that showed everyday heroes, not fighters. In fact, they indicated to Jason Schreier, a notable video game journalist, that Heaven’s Vault was a point of inspiration – and competition.[4] While Heaven’s Vault’s sometimes infuriatingly complex language and niche archaeological style delights me and presumably many of you, they felt it could be streamlined into something more approachable, something with a message of unity.

And, like Heaven’s Vault, Chants of Sennaar is a wonderful game that allows language to lead the way, but it still has to work within the constraints of being a playable video game. There had to be some method of confirming your answers, and this, in my opinion, is where we get some really interesting insight into the true gods of this world – not Exile, but Moya and Panuel.

Our handy journal translates glyphs into familiar English, and I would love to see someone do an analysis of what the confirmation words are in other languages where this game is available. Because in English, we get some fascinating insights. We consistently get the word “man” instead of “human” or “person”, despite the lack of gendered characteristics in most of the people shown in the game, for example. There is no obvious context that shapes the identification of the ideal as “key” for the Alchemists rather than “truth” or perhaps “enlightenment”, but it does give us the key (pun intended) to the door up to the Anchorite level.

The layers of linguistic and cultural interpretation here are fascinating, especially when we come to the last part of the game, the simulation of the tower. Except for the glitches, it is indistinguishable from the real tower, and yet we are also experiencing this from our position outside the screen, knowing there is no real tower. The languages of Exile are fragmentary in our experience, but we, playing the game, know that in the world of the story they must be more complete. And the translation from glyphic to English from there is, necessarily, layered in just as much context as any of these imaginary cultures.

This translation – both among the tower’s languages and between the game and the user’s own language – is a simple mechanic that engages average game-players with linguistic questions normally reserved for more inaccessible contexts. If you can learn to translate between Bards and Alchemists, could you not then take that skill and apply it to, say, Japanese and French? It’s a more complex learning process, but the questions remain the same.

Language-based games like Chants of Sennaar and Heaven’s Vault explore the thing I find the most fascinating about ancient studies and humanity as a whole: communication and connection across time and space. There is a richness to the possibilities these experiences open up within the mechanics of antiquity that I am very eager to see.

Julie Levy (she/they) is an independent scholar, YouTuber, and activist. She currently works as the Managing Director for the Save Ancient Studies Alliance. Their favorite video games include Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Stardew Valley, and Heaven’s Vault. You can watch her archaeogaming streams here or check out her summer series for SASA here Saturdays June and July 2024.

[1] Complex Hanzi characters are made up of multiple radicals, or smaller characters, each of which imparts some amount of meaning to the whole. For instance, the character for day includes both the sun and moon radical. You can learn more here.

[2] Harald Hammarström, Linguistic diversity and language evolution, Journal of Language Evolution, Volume 1, Issue 1, January 2016, Pages 19–29.

[3] Moya, Julien, Deep Dive: The visual tapestry of Chants of Sennaar, Game Developer. November 2023.

[4] Schreier, Jason, Two Hobbyists Made One of This Year’s Best Video Games, Bloomberg. October, 2023.