This post is the second half of a broader discussion on classical reception in Dragon Age.

“Selfish, I suppose. Not to want to spend my entire life screaming on the inside.”

(BioWare, 2014)

In my first entry on the Paizomen blog, I addressed the use of the coding of the Tevinter Empire in the Dragon Age franchise in terms of the Roman Empire. There I showed the way that Tevinter-as-Rome helps to paint Roman/Tevinter imperialism as something toxic, something not to be rewarded, but as an institution that subjugates and enslaves the conquered, and comes to endanger the world itself. One element of Tevinter/Rome’s “decline” that I discussed is specifically linked to their perceived decadence, and while this has long since lost any footing in academia, it is still popularly repeated (in fact, as I was preparing this entry, my own uncle repeated it to me; I responded by sending him Watts’ excellent Eternal Decline and Fall of Rome: The History of a Dangerous Idea).

Now, I am going to turn my attention to two characters who made their debut in Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014), Dorian Pavus and Cremisius “Krem” Aclassi. As two queer characters, they directly relate to the previously-discussed idea of Roman decadence leading to its fall, as this “decadent” argument is often extended to connect Rome’s “fall” to a supposed “moral decline”. Often this moralizing is connected with 2SLGBTQ+ communities. With Dorian especially connected to the player as a character companion whose quest directly relates to the fantasy conversion therapy that he is forced through, BioWare continues to disentangle the myth of imperialism’s value, often seen in video games, by demonstrating that (as I showed in the previous entry) imperialism not only traumatizes and subjugates others, but also its own citizens.

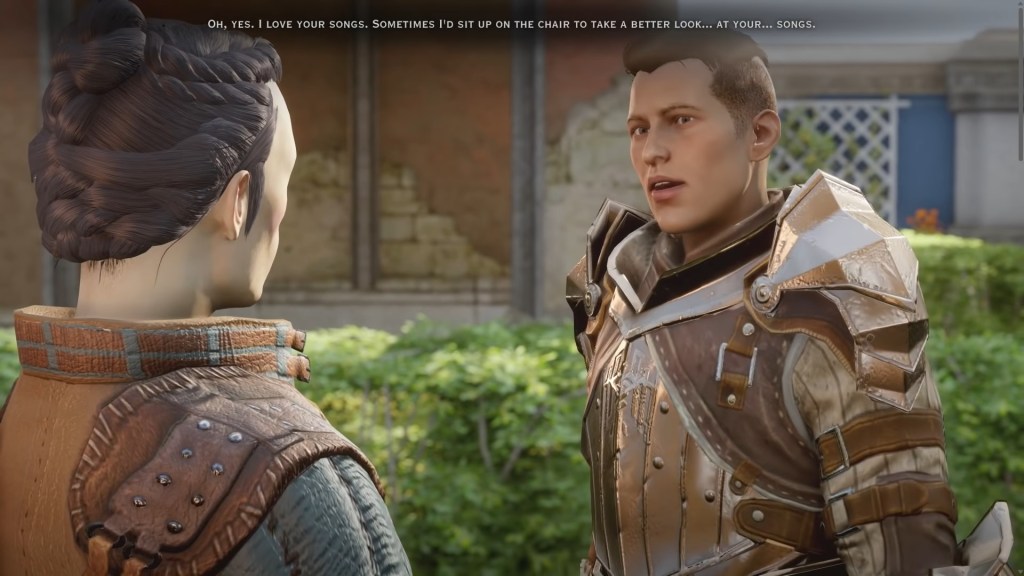

An important component of BioWare games, including Dragon Age, is the involvement of character companions, and it is a key draw for many players. Indeed, each character companion receives individual character quests that expand our knowledge and understanding of these companions, allowing for the game to explore a multiplicity of perspectives that go beyond the avatar’s identity. Yet, as I discussed in my first entry, when Dorian Pavus is first introduced as the first Tevinter character companion in Inquisition, the player is primed to see his nation as deeply troubling. Indeed, the player’s first impression of Dorian plays into stereotypes of Tevinter arrogance when he mocks the player for not understanding their own power, before referring to the “southerners” of Ferelden as “sounding like barbarians”. Yet once the player becomes acquainted with Dorian, he reveals himself to be a deeply sensitive character who has turned against his homeland to do what he thinks is right in resisting Corypheus’ attempts to “restore the Imperium”. Through dialogue with him, players receive their first glimpse within the Imperium and the cultural denial of the dangers of imperial ambition that wipe away the truth of Tevinter’s historical crimes. This even expands to the culpability of Tevinter Magisters in starting the Blight, which I’ve established above as an analogy for the effects of imperial expansion. As Dorian explains:

In Tevinter, they say the Chantry tales of magisters starting the Blight are just that: tales. But here we are: one of those very magisters a Dark Spawn. … I knew what I was taught couldn’t be the whole truth. But I assumed there had to be a kernel of it…somewhere. But no. It was us all along. We destroyed the world.

Indeed, Dorian expresses concern over how his fellow citizens will respond to learning that it was not the Imperium that defeated the former Elven empire, but that it was simply another empire destroyed by corruption and infighting; this fictional historical victory is, in Dorian’s words “ingrained in [Tevinters’] psyche” as something to be proud of. As Said once wrote about imperialist nations (1993: xxvi):

Defensive, reactive, and even paranoid nationalism is, alas, frequently woven into the very fabric of education, where children as well as older students are taught to venerate and celebrate the uniqueness of their tradition…

Thus in learning more about Tevinter from Dorian himself, the player is further warned about buying in to imperialist narratives, such as those presented in other representations of Rome in video games, that seek to privilege imperialist perspectives above others. Indeed, this is a lesson that has broader significance outside of games and ancient Mediterranean studies, as the use of ancient exempla to support fascism, White supremacy, and transphobia are tragically on the rise. With this association between the ancient Mediterranean world and extremists on the Right, it is thus even more important that a warning about accepting imperialist narratives without question be spoken by a character associated with the same ancient world so often used by these bad actors to support their causes (for more on this, see the fantastic work of Pharos, who document and write about these appropriations of antiquity).

Yet Dorian has a far more sophisticated involvement in the game’s discussion of imperialism, particularly in terms of the way he defies traditional narratives of Roman collapse tied to Roman decadence. Indeed in many discussions of Roman decline, this supposed “decadence” has been moralised, representing not just indulgence, but amoral behaviour. As an anonymous writer in the Victorian The Leisure Hour wrote:

The observer cannot but be struck with strange parallels in moral aspect of the Paris of to-day and Rome of the Decadence. … The austere virtues to which Rome was indebted for proud pre-eminence as crowned mistress of the world, were certainly not conspicuous in her, in the days of her decline. Emperors sunk in the softness of Asian indolence, shut within palace walls, ignorant of affairs, governed by women and eunuchs, and consulting with ministers scarcely less effeminate than themselves, could not, with their languid efforts, guide well the state. (1870, 10 December: 788)

In such conceptions, it was not just indulgence and laziness that undermined the empire, but a blurring of gender boundaries manifesting in implied non-heteronormative relationships and behaviours.

Today associations between the “decline” of Rome and a moral decline are certainly not widely entertained in scholarly circles, and yet the prevalence of these ideas still circulate in popular discourse, often as a warning against similar “moral decay” in modern culture. This moral decay is, of course, always somewhat amorphous, making it easy to adopt and exploit; as Drake argues: “…just take whatever problem is bothering you today, add the word ‘Rome’, and voila. You have discovered why the mightiest empire in Western history came to an end” (2019, 3 March). Among these complaints, same-sex desire has repeatedly been targeted as part of this “moral decay” (Watts performs an excellent survey of this narrative throughout history). In a 1984 interview with Playboy, actress Joan Collins even attributed the AIDS pandemic (at the time still linked to the 2SLGBTQ+ community) to imperial collapse: “It’s just like the Roman Empire. Wasn’t everyone just covered in syphilis? And then it was destroyed by the volcano” (quoted by Watts, 2021: 234). More recently in 2011, Italian history professor, Roberto De Mattei claimed: “The collapse of the Roman Empire and the arrival of the Barbarians was due to the spread of homosexuality” (Squires, 2011, 9 April); and only a few years later in 2013, future Secretary of Housing and Urban Development for the US, Ben Carson, opined that homosexuality might have led to Rome’s collapse.

Thus, Dorian Pavus, a character who appears in a game released only one year after Carson’s comments on homosexuality in Rome and whose personal quest deals with a family reconciliation in the wake of fantasy-world conversion therapy, is a powerful inclusion. Indeed, Dorian is, in creator Gaider’s words, the first “legitimately gay” character in the franchise, as other characters romanceable by same-sex player-characters are bisexual (Makuch, 2014, 1 July). Outside of Tevinter, same-sex desire is both normal and celebrated; within a crumbling empire flailing to maintain power, it is a threat to that imperial ideal. Thus Dorian’s father performs human-sacrificing blood magic in an attempt to change his son’s sexual orientation. Dorian explains: “if you’re trying to live up to an impossible standard…every perceived flaw, every aberration is deviant and shameful. It must be hidden.”

Dorian is not the only queer former Tevinter citizen who appears in Inquisition. While not an official companion, Cremisius “Krem” Aclassi is the series’ first trans character and the player frequently encounters him in their home base. A once-impoverished citizen of the Imperium, Krem serves with a band of mercenaries hired by the player early in the game. Outside the Imperium there is no question of Krem’s gender identity; he lives as a man and in some endings in the Trespasser DLC, begins a heterosexual relationship as a man. Within the Imperium, however, while serving with the military as a man, when Krem’s female sex organs were discovered he was forced to flee to avoid either enslavement or execution. Indeed, before the events of Inquisition, Krem is almost killed by a military tribune who wants to “make an example” of him.

Said once commented on the nature of imperialized identities, and the effect of postcolonialism on them:

…new alignments made across borders, types, nations, and essences are rapidly coming into view, and it is those new alignments that now provoke and challenge the fundamentally static notion of identity that has been the core of cultural thought during the age of imperialism (1993: xxiv-xxv).

This is precisely what we see in the characters of Dorian and Krem, both citizens of the Imperium at opposite ends of the power spectrum. In imperial Tevinter there is no space for identities that challenge heteronormative structures in which procreation is an act of refining bloodlines in search of an ideal Tevinter citizen. And by turning two queer characters into icons of imperial resistance, Inquisition expands its critique of common narratives of Roman imperial exceptionalism with a critique of the familiar narratives of “moral decay” and “Roman collapse”. Tevinter did and does not fall because of Dorian or Krem’s identities, just as Rome did not. Instead, the punishing and marginalization of their identities in Tevinter creates a new class of victims that separates families and instills long-standing trauma in its own people. While living outside the Imperium, “new alignments” are revealed that allow for identities that move beyond the static. Thus we see that the collapse of imperial structures that insist on rigid identity is to be celebrated, and the Roman “collapse” often moralised in fact allows for an expansion of identity to be more inclusive. Attempts to cling to imperial ideals, moreover, are deeply traumatizing to even those citizens who ostensibly benefit from that imperialism.

While both direct and semiotic representations of Rome in videogames often valorize imperialism, the Dragon Age franchise has demonstrated that the manipulation of popularly understood ideas from and about Roman history can be used to counter these same valorizations. By introducing Dorian Pavus in Inquisition, and making his sexual orientation and his father’s attempted conversion therapy (through the hated blood magic) a central component of his character quest, players see the way imperial models harm not just those who are conquered but the conquerors too. Indeed, by choosing a topic still used in arguments regarding the moral decline and collapse of Rome (queer acceptance) connected to the very “decadence” of Rome that Tevinter embodies, Inquisition fundamentally turns the “moral decay” argument on its head. Through Dorian and Krem, the player witnesses the reality of restrictive imperial identities that separate and villainise their own people even as others within Tevinter seek to “perfect” themselves and thus restore their historical “glory”. Through Dorian and Krem, the player sees that it is not “moral decay” that leads to societal collapse, but instead it is the very concern with this “decay” that causes separation and fragmentation.

Through a fantasy universe, Dragon Age thus enters into a modern discourse regarding post-colonialism and the effects of empire that demonstrate the damaging potential of imperialism across identities. We see that the tragedy of any imperial structure at its height and during its “fall” is never the fall itself. Instead the tragedy is the victims of imperialism both from positions of power and the conquered “Others” whose identities are marginalized, erased, exploited, and subsumed. In fact, in the aftermath of empire, it is these survivors of imperialism who must rebuild in the face of increasingly extreme attempts to remake the glory of empire that was really no glory at all.

Natalie J. Swain is an assistant professor at Acadia University, Canada. Her research interests include Latin elegy, philology, and narratology, and Classical Reception in modern comics, video games, and narratives of the Polar Regions. Natalie has published and spoken extensively on all of these topics, most recently in Classical Philology and Games and Culture. Natalie is actively involved in the Classical Association of Canada’s Women’s Network, is a founding member of Antiquity in Media Studies, and is actively involved in union-work and fighting for better conditions for contingent faculty, PhD students, and early-career scholars.

Drake, H. A. (2019, 3 March). “Contemporary Lessons from the Fall of Rome.” Oxford University Press Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.oup.com/2019/03/contemporary-lessons-from-the-fall-of-rome/. Accessed on 26 April 2023.

Makuch, Eddie (2014, 1 July). “Dragon Age Inquisition’s Dorian Character is ‘Legitimately Gay,’ BioWare says.” GameSpot. Retrieved from https://www.gamespot.com/articles/dragon-age-inquisition-s-dorian-character-is-legitimately-gay-bioware-says/1100-6420844/. Accessed on 26 April 2023.

(1870, 10 December). “Sack of Rome.” The Leisure Hour: A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation: 788-790.

Said, Edward (1993). Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus.

Squires, Nick (2011, 9 April). “Fall of Roman Empire caused by ‘contagion of homosexuality’.” The Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/8438210/Fall-of-Roman-Empire- caused-by-contagion-of-homosexuality.html. Accessed on 26 April 2023.

Watts, Edward J. (2021). The Eternal Decline and Fall of Rome: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

One thought on “A Warning Against Imperialism #2: Dorian Pavus & Cremisius Aclassi Fight Back in Dragon Age. By Natalie J. Swain”